"PEER BUX," THE TERROR OF HUNSUR.

I consider Kenneth Anderson is a master storyteller in jungle literature. Still, I think he was influenced by some pioneers on this category. At least he may had a good read on Jim Corbett or this person named Mervin A Smith. We can find so many common words and phrases among their books.

The following passages are taken from the book "Sport and adventure in the Indian jungle" by A. MERVYN SMITH published by HURST AND BLACKETT, MARLBOROUGH STREET, London, in 1904. There are many pretty good and exciting chapters in Indian jungle literature, by this author, and I have selected two of them which describes a mad elephant named Peer bux. The Entire location of the story was near to my native place, Mananthavady (Manantoddy) hence I have a personal attachment to this story.

Enjoy the read:

(some words used in the story to denote present spellings:

Kabbany, Kabini = Kabani River

Karkankote = Kankana kote, Bavali, Karapura

Frazerpett = Probably Virajpet, Veerarajapeta, in Coorg.

Heggadavencotta= Hegda Devayar Kotta, HD Kote

Manantoddy=Mananthavady

Potail= Patel (village head/magistrate)

Karkankote = Kankana kote, Bavali, Karapura

Frazerpett = Probably Virajpet, Veerarajapeta, in Coorg.

Heggadavencotta= Hegda Devayar Kotta, HD Kote

Manantoddy=Mananthavady

Potail= Patel (village head/magistrate)

"PEER BUX," THE TERROR OF HUNSUR. I

PEER Bux was the largest elephant in the Madras Government Commissariat Department. He stood nine feet six inches at the shoulder and more than ten feet at the highest point of the convexity of the backbone. His tusks protruded three and a half feet and were massive and solid, with a slight curve upwards and outwards. His trunk was large and massive, while the skin was soft as velvet and mottled red and white, as high-class elephants' should be. His pillar-like fore legs were as straight as a beeline from shoulder to foot, and showed muscle enough for half-a-dozen elephants. Physically Peer Bux was the ideal of elephantine beauty, a brute that should have fetched fifteen thousand rupees in the market and be cheap at that price, for was he, not a grander elephant to look at than many a beast that had cost its princely owner double that sum. He was quiet too and docile, and could generally be driven by a child. Yet with all his good qualities, with all his majestic proportions, Peer Bux was tabooed by the natives. No Hindoo would have him as a gift.

He was a marked beast; his tail was bifurcated at the extremity. This signified, said those natives learned in elephant lore, that he would one clay take human life. When captured in the kheddahs in Michael's Valley, Coimbatore district, the European official in charge of the kheddah operations imagined the animal would bring a fancy price ; but at the public sale of the captured herd no one would give a bid for him, although his tusks alone would have fetched over a 'thousand rupees for their ivory. The fatal blemish the divided tail was soon known to intending purchasers, and there being no bidders he had to be retained or Government use.

The Commissariat Department was justly proud of Peer Bux. He had done good service for six years. Did the heavy guns stick in the mud when the artillery was on its way to Bellary, Peer Bux was sent to assist, and with a push of his massive head, he would lift the great cannon, however deep its wheels might be embedded in the unctuous black cotton soil. Were heavy stores required at Mercara, Peer Bux would mount the steep ghaut road, and think nothing of a ton and a half load on his back.

The Forest Department too found him invaluable in drawing heavy logs from the heart of the reserves. His register of conduct was blameless, and beyond occasional fits of temper during the must season once a year he was one of the most even-tempered as well as one of the most useful beasts in the Transport establishment.

The Commissariat sergeant at Hunsur, who had known Peer Bux for two years, would smile when allusion was made to his bifurcated tail and the native superstition regarding that malformation.

But a little while, and quite another story had to be told of Peer Bux. This pattern animal had gone must. Fazul, his usual mahout (keeper), was not there to manage him (he had gone with Sanderson to Assam), and the new keeper had struck Peer Bux when he showed temper and had been torn limb from limb by the irritated brute.

on the Manantoddy road; had overturned coffee carts and scattered their contents on the road; had killed several cart-men; had looted several villages and torn down the huts.

In fact a homicidal mania seemed to have come over him, as he would steal into the cholum (sorghum millet) fields and pull down the machans (bamboo platforms) on which the cultivator sat watching his corn by night, and tear the poor wretch to pieces or trample him out of all shape, and it

was even said that in his blind rage he would eat portions of his human victims. I may here mention that natives firmly believe that elephants will occasionally take to man-eating. It is a common practice when a tiger is killed for the mahouts to dip balls of jaggery (coarse sugar) in the tiger's blood and feed the elephants that took part in the drive with this mess. They say the taste of the tiger's blood gives the elephant courage to face these fierce brutes. The taste for blood thus acquired sticks to the elephant, and when he goes mad or must and takes to killing human beings, some of their blood gets into his mouth and reminds him of the sugar and blood given him at the tiger-hunts, and he occasionally indulges in a mouthful of raw flesh.

Was Peer Bux must, or was he really mad? The mahouts at Hunsur, who knew him well, said he was only must. Europeans frequently speak of must elephants as" mad "elephants, as though the two terms were synonymous. Must, I may state, is a periodical functional derangement common to all bull elephants, and corresponds to the rutting season with deer and other animals. It generally occurs in the male once a year (usually in March or April), and lasts about two or three months.

Was Peer Bux must, or was he really mad? The mahouts at Hunsur, who knew him well, said he was only must. Europeans frequently speak of must elephants as" mad "elephants, as though the two terms were synonymous. Must, I may state, is a periodical functional derangement common to all bull elephants, and corresponds to the rutting season with deer and other animals. It generally occurs in the male once a year (usually in March or April), and lasts about two or three months.

During this period a dark-colored mucous discharge oozes from the temples. If this discharge is carefully washed off twice a day, and the elephant is given a certain amount of opium with his food and made to stand up to his middle in water for an hour every day, beyond a little uneasiness and irritability in temper no evil consequences ensue ; but should these precautions be neglected, the animal becomes savage and even furious for a time, so that it is never safe to approach him during these periods.

When an elephant shows signs of must the dark discharge at the temples is an infallible sign he should always be securely hobbled and chained. A musth elephant, even when he breaks loose and does a lot of damage, can if recaptured be broken to discipline and will become as docile as ever, after the must period is passed.

It is wholly different from a mad elephant. These brutes should be destroyed at once, as they never recover their senses, the derangement in their case being cerebral and permanent, and not merely functional. This madness is frequently due to sunstroke, as elephants are by nature fitted to live under the deep shade of primeval forests.

In the wild state, they feed only at night when they come out into the open. They retire at dawn into the depths of the forests, so that they are never exposed to the full heat of the noonday sun.

Peer Bux being the property of the Madras Government, permission was asked to destroy him, as he had done much damage to life and property in that portion of the Mysore territory lying between Hunsur and the frontier of Coorg and North Wynaad.

The Commissariat Department, however, regarded him as too valuable an animal to be shot and advised that some attempt should be made to recapture him with the aid of tame elephants. Several trained elephants were sent up from Coimbatore, some more were obtained from the Mysore State, and several hunts were organised, but all attempts at his recapture entirely failed. The great length of

his fore-legs gave Peer Bux an enormous stretch so that he could easily outpace the fleetest shikar elephants; and when he showed fight, none of the tuskers, not even the famous Jung Bahadoor, the fighting elephant of the Maharaja of Mysore, could withstand his charge.

|

| Royalty on Tour The Prince of Wales Tiger Shooting with Jung Bahadoor ; India |

|

| Meanwhile so great was the terror he inspired that nearly all traffic was stopped between Hunsur and Coorg, and Mysore and Manantoddy. |

He had been at large now for nearly two months, and in that time was known to have killed fourteen persons, wrecked two villages, and done an incredible amount of damage to traffic and crops.

Permission was now obtained to destroy him by any means, and a Government reward was offered to anyone who would kill the brute.

Several parties went out from Bangalore in the hope of bagging him, but never got sight of him. He was here today, and twenty miles off the next day. He was never known to attack Europeans. He would lie in wait in some unfrequented part of the road and allow any suspicious-looking object to pass ; but when he saw a line of native carts, or a small company of native travellers, he would rush out with a cream and a trumpet and overturn carts and kick them to pieces, and woe betide the unfortunate human being that fell into his clutches ! He would smash them to a pulp beneath his huge feet, or tear them limb from limb.

|

They were engaged in a shooting trip along that belt of forest which forms the boundary between Mysore and British territory to the south-west.

|

Our shoot thus far had been very unsuccessful. Beyond a few spotted deer and some game birds, we had bagged nothing.

|

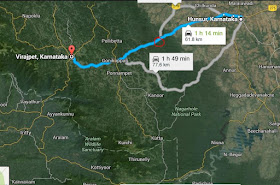

Much of the above information regarding Peer Bux was gleaned at the Dak Bungalow (travelers'

rest-house-Marked in Green Circle) at Hunsur, where a party of four, including myself, were staying there.

|

The Government notification of a reward for the destruction of the rogue-elephant stared us in the face at every turn we took in the long, cool verandah of the bungalow. We had not come out prepared for elephant-shooting, yet there was a sufficiency of heavy metal in our armoury, we thought, to try conclusions with even so formidable an antagonist as Peer Bux, should we meet with him. Disgust at the want of success hitherto of our shikar expedition, and the tantalizing effects of the Government notice showing that there was a game very much in evidence if we cared to go after it, soon determined our movements.

|

| The native shikaris were summoned, and after much consultation we shifted camp to Karkankotee, a smaller village in the State forest of that name, and on the high road to Manantoddy. |

The native shikaris were summoned, and after much consultation, we shifted camp to Karkankotee, a smaller village in the State forest of that name, and on the high road to Manantoddy. The travelers' bungalow .there, a second-class one, was deserted by its usual native attendants, as the rogue - elephant had paid two visits to that place and had pulled down a portion of the out-offices in his attempts to get at the servants. In the village we found only a family of Kurambas left in charge by the Potail (village magistrate) when the inhabitants deserted it. These people, we found, had erected for themselves a machan (platform) on the trees, to which they retired at night to be out of the reach of the elephant, should he come that way. From them, we learned that the rogue had not been seen for a week, but that it was about his time to come that way, as he had a practice of making a complete circuit of the country lying between the frontier and the Manantoddy-Mysore and Hunsur-Mercara roads. This was good news, so we set to work at once, getting ammunition ready for this the

largest of all game. Nothing less than eight grams of powder and a hardened solid ball would content

most of us. K , poor fellow, had been reading up " Smooth-bore "or some other authority on Indian game, and pinned his faith to a twelve bore duck gun,"for," he argued, "at twenty paces " and that was the maximum distance from which to shoot at an elephant" the smooth-bore will shoot as straight as the rifle and hit quite as hard."

We were in bed betimes, as we meant to be up at daybreak and have a good hunt all round, under the guidance of the Kurambas, who promised to take us to the rogue's favourite haunts when in that neighbourhood. The dak-bungalow had but two rooms. That in which O - and myself slept had a window overlooking the out-offices. In the adjacent room slept F and K .

Towards the small hours of the morning, I was awakened by a loud discharge of fire-arms from F- 's room, followed by the unmistakable fierce trumpeting of an enraged elephant. There is no mistaking that sound when once heard. Catching up our rifles we rushed into the next room and found F, gun in hand, peering out through the broken window frame, and K - trying to strike a light. When F- - had recovered sufficiently from his excitement, he explained that he had been awakened by something trying to encircle his feet through the thick folds of the rug he had wrapped around them. On looking up he thought he could make out the trunk of an elephant thrust through the opening where a pane of glass had been broken in the window. His loaded gun was in the corner by his side, and, aiming at what he thought would be the direction of the head, he fired both barrels at once. With a loud scream, the elephant withdrew its trunk, smashing the whole window at the same time. He had reloaded and was looking out for the elephant, in case it should return to the attack, but could see nothing, as it was too dark. F- -'s was a narrow escape, for had the elephant succeeded in getting his trunk around one of his legs nothing could have saved him. With one jerk he would have been pulled through the window and quickly done to death beneath the huge feet of the brute. The thick folds of the blanket alone saved him, and even that would have been pulled aside in a little time if he had not awakened and had the presence of mind to fire at the beast.

Towards the small hours of the morning, I was awakened by a loud discharge of fire-arms from F- 's room, followed by the unmistakable fierce trumpeting of an enraged elephant. There is no mistaking that sound when once heard. Catching up our rifles we rushed into the next room and found F, gun in hand, peering out through the broken window frame, and K - trying to strike a light. When F- - had recovered sufficiently from his excitement, he explained that he had been awakened by something trying to encircle his feet through the thick folds of the rug he had wrapped around them. On looking up he thought he could make out the trunk of an elephant thrust through the opening where a pane of glass had been broken in the window. His loaded gun was in the corner by his side, and, aiming at what he thought would be the direction of the head, he fired both barrels at once. With a loud scream, the elephant withdrew its trunk, smashing the whole window at the same time. He had reloaded and was looking out for the elephant, in case it should return to the attack, but could see nothing, as it was too dark. F- -'s was a narrow escape, for had the elephant succeeded in getting his trunk around one of his legs nothing could have saved him. With one jerk he would have been pulled through the window and quickly done to death beneath the huge feet of the brute. The thick folds of the blanket alone saved him, and even that would have been pulled aside in a little time if he had not awakened and had the presence of mind to fire at the beast.

No amount of shouting would bring any of the servants from their retreat in the out-office, although we could distinctly hear them talking to each other in low tones; and it was scarcely fair of us to ask them to come out, with the probability of an infuriated rogue elephant being about. However, we soon remembered this fact, and helping ourselves to whiskey pegs, as the excitement had made us thirsty, we determined to sit out the darkness, as nothing could be done till morning.

At the first break of day, we sallied out to learn the effects of F- -5 s shots. We could distinctly trace the huge impressions of the elephant's feet to the forest skirting the bungalow, but could findno trace of blood. The Kuramba trackers were soon on the spot, and on matters being explained to them they said the elephant must be badly wounded about the face, otherwise, he would have renewed the attack. The shots being fired at such close quarters must have scorched the opening of the wound and prevented the immediate flow of blood. They added that if wounded the elephant would not go far, but would make for the nearest water in search of mud with which to plaster the wound, as the mud was a sovereign remedy for all elephant wounds, and all elephant used it. The brute would then lie up in some dense thicket for a day or two, as any exertion would tend to re-open the wound. The Kurambas

appeared to be so thoroughly acquainted with the habits of these beasts, that we readily placed ourselves under their guidance, and swallowing a hasty breakfast we set off on the trail, taking with us one shikar to interpret and a gun-bearer, named Suliman, to carry a tiffin-basket.

The tracks ran parallel with the road for about a mile, and then crossed it and made south in the direction of the Kabbany river, an affluent of the Cauvery. Distinct traces of blood could now be seen, and presently we came to a spot covered with blood, where the elephant had evidently stood for some time. The country became more and more difficult as we approached the river. Dense clumps of bamboo and wait-a-bit thorns, with here and there a large teak or honne tree, made it difficult to see more than a few yards ahead. The Kuramba guides said that we must now advance more cautiously, as the river was within half a mile, and that we might come on the" rogue "at any moment. Up to this

moment, I don't know if any of us appreciated the full extent of the danger we were running.

Following up a wounded must elephant on foot, in dense cover such as we were in, meant that if we did not drop the brute with the first shot, one or more of us would in all probability pay for our temerity with our lives. We had been on the tramp two hours and we were all of us more or less excited, so taking a sip of cold tea to steady our nerves, we settled on a plan of operations.

F - and I, having the heaviest guns, were to lead, the Kuramba trackers being a pace or two in advance of us. O and K were to follow about five paces behind, and the shikari and Suliman were to bring up the rear at an interval of ten paces. If we came on the elephant, the advance party were to fire first and then move aside. If the brute survived our fire, the second battery would surely account for it. It never entered our minds that anything living could withstand a discharge at close quarters of eight such barrels as we carried. Having settled matters to our satisfaction, off we set on the trail, moving now very cautiously, the guides enjoining the strictest silence. Every bush was carefully examined, every thicket scanned before an advance was made ; frequent stops were made, and the drops of blood carefully examined to see if they were clotted or not, as by this the Kurambas could tell how far off the wounded brute was.

|

| Present Condition the stretch of road to Bavali, at somewhere described in the passage, on Mysore Mananthavady road. |

|

| An elephant is almost invisible to our camera |

The excitement was intense. The rustle of a falling leaf would set our hearts pit-a-pat. The nervous

the strain was too great, and I began to feel quite sick.

The trail now entered a cart-track through the forest, so that we could see twenty paces or so ahead. Now we were approaching the river, for we could hear the murmuring of the water some two or three hundred yards ahead. The bamboo clumps grew thicker on either side. The leading Kuramba was just indicating that the trail led off to the right when a terrific trumpet directly behind us made us start round, and a ghastly sight met our view.

It had quietly allowed us to pass, and then, uttering a shrill scream, charged on the rear. Seizing Suliman in its trunk, it had lifted him aloft prior to dashing him to the ground, when we turned. K was standing in the path, about ten paces from the elephant, with his gun, leveled at the brute.

"Fire, K , fire !

' we shouted,but it was too late. Down came the trunk, and the body of poor Suliman, hurled with terrific force, was dashed on the ground with a sickening thud, which told us he was beyond help. As the trunk was coming down K - fired. In a moment the enraged brute was on him. We heard a second shot, and then saw poor K- - and his gun flying through the air from a kick from the animal's

' we shouted,but it was too late. Down came the trunk, and the body of poor Suliman, hurled with terrific force, was dashed on the ground with a sickening thud, which told us he was beyond help. As the trunk was coming down K - fired. In a moment the enraged brute was on him. We heard a second shot, and then saw poor K- - and his gun flying through the air from a kick from the animal's

forefoot. There was no time to aim. Indeed, there was nothing to aim at, as all we could see was a great black object coming down on us with incredible speed. Four shots in rapid succession and the brute swerved to the left and went off screaming and crashing through the bamboos in its wild flight. Rapidly reloading we waited to see if the rogue would come back, but we heard the crashing of the underwood further off and knew it had gone for good. We had now time to look round. The body of K - we found on the top of a bamboo clump a good many yards away.

We thought he was dead, as he did not reply to our calls, but on cutting down the bamboos and removing the body we found he had only swooned. A glass of whisky soon brought him round, but he was unable to move, as his spine was injured and several ribs were broken. Rigging a hammock, we had him carried into Manantoddy, where he was on the doctor's hands for months before he was able

to move, and finally he had to go back to England and, I believe, never thoroughly recovered his health. Suliman's corpse had to be taken into Antarasante, and after an inquest, by the native Magistrate it was made over to the poor fellow's co-religionists for burial. The subsequent history of Peer Bux how he killed two English officers and afterward met his own fate I must reserve for another chapter.

to move, and finally he had to go back to England and, I believe, never thoroughly recovered his health. Suliman's corpse had to be taken into Antarasante, and after an inquest, by the native Magistrate it was made over to the poor fellow's co-religionists for burial. The subsequent history of Peer Bux how he killed two English officers and afterward met his own fate I must reserve for another chapter.

THE TERROR OF HUNSUR. II.

OUR tragic adventure with Peer Bux, the rogue elephant, related in the last chapter, was soon noised abroad and served only to attract a greater number of British sportsmen, bent on trying conclusions with the " Terror of Hunsur," as this notorious brute came to be called by the inhabitants of the adjacent districts. A month had elapsed since our ill-fated expedition, and nothing had been heard of the rogue, although its known haunts had been scoured by some of the most noted shikars of South India. We began to think that the wounds it had received in its encounter with us had proved fatal, and even contemplated claiming its tusks should its carcass be found, and presenting them to K - as a memento of his terrible experience with the monster, but it was a case of "counting your chickens," for evidence was soon forthcoming that its tusks were not to be had for the asking.

The beast had evidently been lying low while its wounds healed, and had retreated for this purpose

|

| Nagarhole National park starts from here. Mysore- Mananthavady road |

into some of the dense fastnesses of the Begur jungles. Among others who arrived on the scene; at this time to do battle with the Terror were two young officers from Cannanore one a sub alternin a native regiment, the other a naval officer on a visit to that station. They had come with letters of introduction to Colonel M in charge of the Amrat Mahal at Hunsur, and that officer had done all in his power to dissuade the youngsters from going after the "rogue/' as he saw plainly that they were green at shikar and did not fully comprehend the risks they would be running, nor had they experience enough to enable them to provide against possible contingencies. Finding however that dissuasion only strengthened their determination to brave all danger, he thought he would do the next best thing by giving them the best mount possible for such a task.

|

| A kumki elephant in the same area. |

Among the recent arrivals at the Commissariat lines was " Dod Kempa" (the Great Red One), a famous tusker sent down all the way from Secunderabad to do battle with Peer Bux.

Dod Kempa was known to be staunch, as he had been frequently used for tiger-shooting in the notorious Nirmul jungles and had unflinchingly stood the charge of a wounded tiger. His mahout

declared that the Terror of Hunsur would run at the mere sight of Dod Kempa, for had not his reputation gone forth throughout the length and breadth of India, even among the elephant-folk ?

Kempa was not as tall as Peer Bux, but was more sturdily built, with short, massive tusks. He was mottled all over his body with red spots: hence his name Kempa (red). He was a veritable bull-dog among elephants and was by no means a handsome brute, but he had repeatedly done good service in bringing to order recalcitrant pachyderms, and for this reason, had been singled out to try conclusions with the Hunsur rogue. With such a mount Colonel M- - thought the young fellows would be safe even should they meet the"Terror/' so seeing them safely mounted on the pad he bid them not to fail to call on D -, the Forest officer on the Coorg frontier, who would put them up to the best means of finding the game they were after.

The elephant and mahout had turned up sometime during the night; the pad had been left behind, and the man could give no information about the two sahibs who had gone out with him. Fearing the worst, the Colonel sent for the mahout, but before the order could be carried out, a crowd of mahouts (elephant drivers) and other natives were seen approaching, shouting

"Pawgalee hogiya / Pawgalee hogiya / (he has gone Mad ! he has gone mad !)."

Yes, sure enough, there was Dod Kempa's mahout inanely grinning and shaking his hands. Now and again he would stop and look behind, and a look of terror would come into his eyes. He would crouch down and put his hands to his ears as if to shut out some dreadful sound. He would remain like this for a minute or two, glance furtively around, and then as if reassured would get up and smile and shake his hands. It was plainly not liquor that made him behave in this manner; the poor fellow had actually become an imbecile through fear. It was hopeless attempting to get any information from such an object, so handing him over to the care of the medical officer, a search party mounted on elephants was at once organised and sent off in the direction of Frazerpett, twenty-four miles distant, where D J s camp was.

On coming up with the cart and examining its contents a most gruesome sight met their eyes. There, rolled up in a native kumbly (blanket), was an indistinguishable mass of human flesh, mud, and clothing.

Crushed out of all shape, the bodies were inextricably mixed together, puddled into one mass by the great feet of the must elephant. None dared touch the shapeless heap, where naught but the boot-covered feet were distinguishable to show that two human beings lay there. A deep gloom fell on all, natives and Europeans alike; none dared speak above a whisper, and in silence the search party turned back, taking with them what was once two gallant young officers, but now an object that made anyone shudder to look at. The forest ranger's story was soon told: he had been an eye-witness of the tragic occurrence. Here it is :-

' They left their camp-followers and baggage at Periyapatna, and accompanied only by himself (the ranger) and the native who brought the information, they rode out on Dod Kempa, took their places on the machan, and sent the mahout back with the elephant with orders for him to come back at dawn next day to take them back to camp. The tiger did not turn up that night, and the whole party were on their way back to Periyapatna in the early dawn, when suddenly Dod Kempa stopped, and striking the ground with the end of his trunk, made that peculiar drumming noise which is the usual signal of alarm with these animals when they scent tiger or other danger. It was still early morning, so that they could barely see any object in the shadow of the forest trees. The elephant now began to back, curl away from his trunk, and sway his head from side to side. The mahout said he was about to charge, and that there must be another elephant in the path. We could barely keep our seats on the pad, so violent was the motion caused by the elephant backing and swaying from side to side.

The officers had to hold on tight by the ropes so that they could not use their guns, when they're in the distance, only fifty yards off, we saw an enormous elephant coming towards us! There was no doubt that it was the rogue, from its great size. It had not seen us yet, as elephants see very badly; but Dod Kempa had scented him out as the wind was in our favour. The Sahibs urged the mahout to keep his elephant quiet so that they might use their guns, but it was no use, for although he cruelly beat the beast about the head with his iron goad yet it continued to back and sway. The rogue had now got within thirty yards, when it perceived us and stopped. It backed a few paces and with ears thrown forward uttered trumpet after trumpet and then came full charge down on us. No sooner did Dod Kempa hear the trumpeting than he turned around and bolted off into the forest, crashing through the brushwood and under the branches of the large trees, the must elephant in hot pursuit.

Suddenly an overhanging branch caught in the side of the pad, ripped it clean off the elephant's back, and threw the two officers on the ground. I managed to seize the branch and clambered up out of harm's way. When I recovered a little from my fright, I saw the rogue elephant crushing something up under its fore feet. Now and again it would stoop and drive its tusks into the mass and begin stamping on it again. This it did for about a quarter of an hour. It then went off in the direction that Dod Kempa had taken. I saw nothing of Dod Kempa after the pad fell off. I waited for two hours, and seeing the mad elephant did not come back, I got down and ran to Periyapatna and told the Sahibs' servants, and we went back with a lot of people, and found that the mass the elephant had been crushing under its feet was the bodies of the two officers ! The brute must have caught them when they were thrown to the ground and killed them with a blow of its trunk or a crush of the foot, and it had then mangled the two bodies together. We got a cart and brought the bodies away."

Simple in all its ghastly details, the tale was enough to make one's blood run cold, but heard as it was, said one present,

"within a few yards of what that bundle of native blankets contained, it steeled one's heart for revenge." But let us leave this painful narrative and hasten on to the time when the monster met with his deserts at the hand of one of the finest sportsmen that ever lived, and that too in a manner which

makes every Britisher feel a pride in his race that can produce such men.

Gordon Gumming was a noted shikari, almost as famous in his way as his brother, the celebrated lion-slayer of South Africa, and his equally famous sister, the talented artist and explorer of Maori fastnesses in New Zealand. Standing over six feet in his stockings and of proportionate breadth of shoulder, he was an athlete in every sense of the word. With his heavy double rifle over his

shoulder, and with Yalloo, his native tracker and shikari at his heels, he would think nothing of a twenty-mile swelter after a wounded bison even in the hottest weather. An unerring shot, he was known to calmly await the furious onset of a tiger till the brute was within a few yards, and then lay it low with a ball crashing through its skull. It is even said that, having tracked a noted man-eater to its lair, he disdained to shoot at the sleeping brute, but roused it with a stone and then shot it as it was making at him open-mouthed. He was known to decline to take part in beats for a game or to use an elephant to shoot from, but would always go alone save for his factotum Yalloo, and would follow up the most dangerous game on foot. He was a man of few words and it was with the greatest difficulty he could be got to talk of his adventures. When pressed to relate an incident in which it was known that he had done a deed of the utmost daring, he would dismiss the subject with half-a-dozen words, generally :

|

| Track Inside Nagerhole forest |

"Yes, the beast came at me, and I shot him." Yalloo was as loquacious as his master was reticent, and it was through his glibness of tongue around the camp fire, that much of Gordon Gumming's shikar doings became known. Yalloo believed absolutely in his taster and would follow him anywhere.

" HE carries two deaths in his hand and can place them where he likes (alluding to his master's accuracy with the rifle) ; therefore, why should I fear? Has a beast two lives that I should dread him? A single shot is enough, and even a Rakshasha (giant demon) would lie low."

A Deputy Commissioner in the Mysore service, Cumming was posted at Shimoga, in the north-west

of the province, when he heard of the doings of Peer Bux at Hunsur, and obtained permission to try and bag him. He soon heard all the khubber (news) as to the habits of the brute, and he determined to systematically stalk him down. For this purpose, he established three or four small camps at various points in the districts ravaged by the brute, so that he might not be hampered with a camp following him about but could call in at any of the temporary shelters he had put up and get such refreshment as he required.

He knew it would be a work of days, perhaps weeks, following up the tracks of the rogue, who was here to-day and twenty miles off to-morrow; but he had confidence in his own staying powers, and he trusted to the chapter of lucky accidents to cut short a toilsome stalk.

Selecting the banks of the Kabbany as the most likely place to fall in with the tracks of Peer Bux, he made Karkankote his resting-place for the time, while a careful examination was made of the ground

on the left bank of the river. Tracks were soon found, but these always led to the river, where they were lost, and no further trace of them was found on either bank. He learned from the Kurambas

that the elephant was in the habit of entering the river and floating down for a mile or so before it made for the banks. As it travelled during the night and generally laid up in dense thicket during the day, there was some chance of coming up with it, if only the more recent tracks could be followed up uninterruptedly ; but with the constant breaks in the scent whenever the animal took to the water he soon saw that tracking would be useless in such country, and that he must shift to where there were no large streams.

|

| A couple of weeks had been spent in the arduous work of following up the brute from Karkankote to Frazerpett and back again to the river near Hunsur and then on to Heggadavencotta. |

Even the tireless Yalloo now became wearied and began to doubt the good fortune of his master. Yet Gordon Cumming was as keen as ever, and would not give up his plan of following like a sleuth-hound on the tracks of the brute. On several occasions they had fallen in with other parties out on the same errand as themselves, but these contented themselves with lying in wait at certain points the brute was known to frequent. These parties had invariably asked Gordon Cumming to join them, as they pronounced his stern chase a wild goose one and said he was as likely to come up with the Flying Dutchman as he was with the Terror of Hunsur.

Even the tireless Yalloo now became wearied and began to doubt the good fortune of his master. Yet Gordon Cumming was as keen as ever, and would not give up his plan of following like a sleuth-hound on the tracks of the brute. On several occasions they had fallen in with other parties out on the same errand as themselves, but these contented themselves with lying in wait at certain points the brute was known to frequent. These parties had invariably asked Gordon Cumming to join them, as they pronounced his stern chase a wild goose one and said he was as likely to come up with the Flying Dutchman as he was with the Terror of Hunsur.

It was getting well into the third week of this long chase, when the tracks led through some scrub jungle which would not give cover to anything larger than a spotted deer.

|

| Machur near to D.B.Kuppe or Dodda Byrankuppe is a small village on the bank of Kabani rive Mysore-Mananthavady road. |

They had come on to the ruins of an ancient village, the only signs of which were a small temple fast falling into decay, and an enormous banyan tree (Ficus religiosa). ((I ASSUME this spot is now located at a village called Machur, near to DB kuppe. There were some remnants of the old temple and a large banyan tree on the very way to river Kabani from Mysore-Mananthavady road.)) It was midday; the heat was intense, and they sat under the shade of the tree for a little rest. Cumming was munching a biscuit, while Yalloo was chewing a little pan (betel-leaf), when a savage scream was heard and there, not twenty paces off, was the Terror of Hunsur coming down on them in a terrific charge. From the position in which Gumming was sitting a fatal shot at the elephant was almost impossible, as it carried its head high and only its chest was exposed. A shot there might rake the body without touching lungs or heart, and then the brute would be on him. Without the least sign of haste and with the utmost unconcern Gordon Gumming still seated, flung his sola topee (sun hat) at the beast when it was about ten yards from him. The rogue stopped momentarily to examine this strange object, and lowered its head for the purpose. This was exactly what Gumming wanted, and quick as thought a bullet, planted in the center of the prominence just above the trunk, crashed through its skull, and the Terror of Hunsur dropped like a stone, shot dead.

They had come on to the ruins of an ancient village, the only signs of which were a small temple fast falling into decay, and an enormous banyan tree (Ficus religiosa). ((I ASSUME this spot is now located at a village called Machur, near to DB kuppe. There were some remnants of the old temple and a large banyan tree on the very way to river Kabani from Mysore-Mananthavady road.)) It was midday; the heat was intense, and they sat under the shade of the tree for a little rest. Cumming was munching a biscuit, while Yalloo was chewing a little pan (betel-leaf), when a savage scream was heard and there, not twenty paces off, was the Terror of Hunsur coming down on them in a terrific charge. From the position in which Gumming was sitting a fatal shot at the elephant was almost impossible, as it carried its head high and only its chest was exposed. A shot there might rake the body without touching lungs or heart, and then the brute would be on him. Without the least sign of haste and with the utmost unconcern Gordon Gumming still seated, flung his sola topee (sun hat) at the beast when it was about ten yards from him. The rogue stopped momentarily to examine this strange object, and lowered its head for the purpose. This was exactly what Gumming wanted, and quick as thought a bullet, planted in the center of the prominence just above the trunk, crashed through its skull, and the Terror of Hunsur dropped like a stone, shot dead.

"Ah, comrade," said Yalloo, when relating the story,"

I could have kissed the Bahadoor's (my lord's) feet when I saw him put the gun down, and go on eating his biscuit just as if he had only shot a bird of some kind, instead of that devil of an elephant. I was ready to die of fright ; yet here was the Sahib sitting down as if his life had not been in frightful jeopardy just a moment before. Truly,the Sahibs are great !