Beypore

Located at the mouth of the Chaliyar River in Kozhikode district, Beypore, one of the prominent ports and fishing harbours of ancient Kerala was an important trade and maritime centre. Ancient Beypore was much sought after by merchants from Western Asia, for its shipbuilding industry. The boat building yard here is famous for the construction of the Uru, the traditional Arabian trading vessel.

The Beypore Beach has a bridge built nearly 2 kms into the sea. It is actually made up of huge stones piled together for nearly 2 kms making a pathway into the sea.

Alternate names

The place was formerly known as Vaypura

formerly known as also: Vadaparappanad.

Tippu Sultan named the town “Sultan Pattanam”.

Beypore port

It is one of the oldest ports in Kerala from where trading was done to the Middle East. Beypore is also famous for building wooden ships, called Dhows or Urus. . According to Captain Iwata, Sumerian ships might have been built in Beypore. There is evidence to prove that Beypore had direct trade links with Mesopotamia and was a prominent link on the maritime silk route.

History

Beypore was ruled by four Kovilakams - Karippa Puthiyakovilakam, Manayat Kovilakam, Nediyaal Kovilakam and Panagad Kovilakam. Considering that Ravi Varma and his brother mentioned Beypore and the specific Manayyat location, let us for a moment assume Raja Ravi Varma hailed from the forerunners of the present Manayyat kovilakom.

It is believed that the Beypore Siva Temple protects the whole kingdom.

Beypore was thronged first by Romans and afterwards by Chinese, Syrians, Arabs and in recent centuries by Europeans for trade. Beypore has a long history of being a centre for shipbuilding since the first century AD, and it was further expanded under the East India Company during the early nineteenth century. The Indian Ocean trade started in ancient times and strengthened during medieval times. While in the old days Malabar directly traded with the Greeks and Romans, it concentrated on exchanges with the Middle Eastern ports in the medieval times. This exchange of goods resulted also in the transfer of people from their abodes. While it is mentioned that Malabari’s were found along with African ports and even Egypt’s, it was mostly Arabs who migrated to the Malabar coasts, mainly to administer, control and conduct the trade with their brethren in Yemen, Basra and Egyptian ports. Beypore was a virtually free port with only an export-import duty imposed by the ruling Zamorins. The intermediaries between the Arabs and the Nairs were the Moplah’s (themselves a community started by the intermingling Arab men and local women from ancient times). Also, the south-east Malay ports sent ships to Malabar for the cloth from Kerala, until British cloth took its place later in the 19th century. It was also a stopover for Hajj pilgrims from south east Asia. The Arab settlers in Malabar even had African slaves during that period.

Beypore Siva Temple

It is believed that the Beypore Siva Temple protects the whole kingdom.

South view of the inner shrine, Mahadevasvami Temple, Beypore, Calicut taluk, Malabar district, photo dated 1900

North-east view of Mahadevasvami Temple, Beypore, Calicut, photo dated 1900 (BELOW)

|

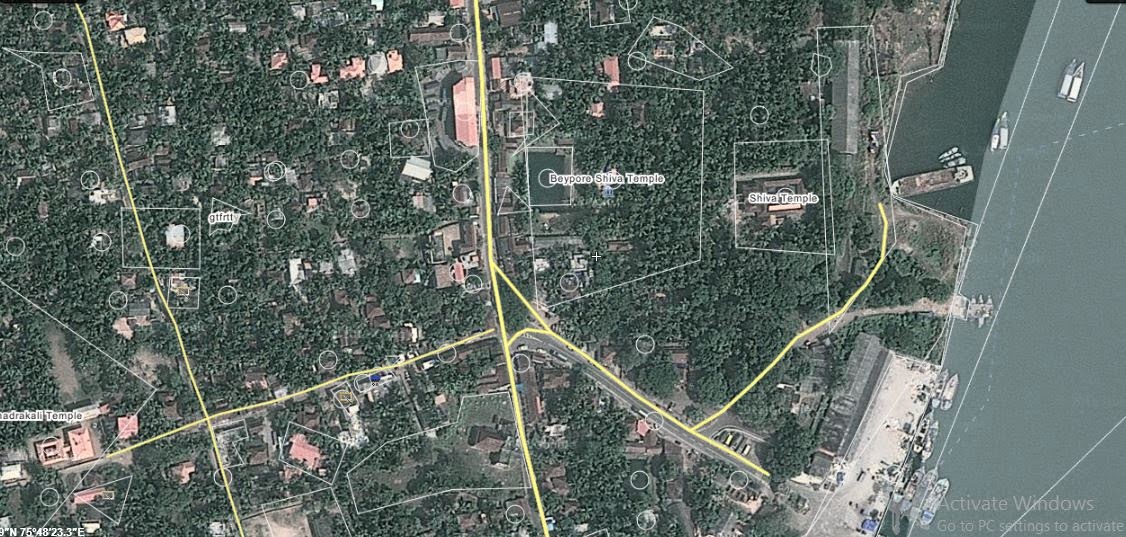

BRadrakaali temple beypore http://wikimapia.org/#lang=en&lat=11.167303&lon=75.803876&z=19&m=b |

The glorious tradition of boat building The flagship of the British Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson who defeated Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 was made in Beypore, not to mention numerous other vessels of his celebrated fleet. Sturdy wooden barges that plied the Suez Canal during the reign of Cleopatra are said to have been made at Beypore. And the flagship of the British Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson who defeated Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 was made in Beypore too, not to mention numerous other vessels of his celebrated fleet. Distinguished antiquity such as this has earned Beypore a strong foothold in Indian maritime history. Known variously as dhow or Uru in Arabic and Paikappal in Malayalam, these indigenous vessels have a striking feature that sets them apart from other sail ships: These legendary crafts are made exclusively of wood, and built without the use of any machines or power tools — only hand tools and indigenous devices are ever used. From sawing the wood to cutting and shaping to assembly and finishing, all operations are done manually, and what’s more, this expertise and skill is handed down the generations only through practical apprenticeship and tutelage. But hold on. Here’s the shocker: No formal plan, designs, sketches or illustrations are ever made to make even a huge vessel. All computations and reckoning to finalise the physical characteristics of the finished vessels are always at the fingertips of the foreman and generally carried in a verse form, each stanza denoting a detailed description of a part of the ship. A mid-sized vessel would require 500 Cft of teak alone and 7500 Cft of other woods like Anjili and Thambakam. Two tons of long, galvanised nails to hold it all together, 100 kg of brass fittings to embellish the vessel and bales of caulking cord, cashew resins and other native ingredients constitute the hardware. And how long would it take to build a vessel designed to carry more than 600 tons of cargo? Carpenters, blacksmiths, caulkers, painters and numerous other labourers toil for up to two years under makeshift roofs. Yet every vessel built here carries a guarantee of at least 75 years. Once complete, launching of these vessels is another study in native ingenuity and resourcefulness. The legendary Khalasis of Malabar has for long carved a niche for themselves in this fine art of launching a completed ship — using nothing more than wooden keel rails and circular blocks of wood. Ropes, pulleys, dextrous arms and sheer brawn do the jobs of cranes and barges and launch a vessel skilfully with nary a mishap. Derived from the Arabic word Khalas meaning release, the word Khalasi is now used both in Malayalam and in Hindi, to refer to anyone who releases a ship or boat into the water. The Khalasis of Malabar engaged in boat building and boat repair use simple but cleverly designed types of equipment and devices put together by ancestors that leverage muscular strength quite amazingly. Though education is hardly their strength, what they have in abundance is natural wisdom and simple common sense. Deceptively simple wooden winches called davars and long wooden handles called kazhas work wonders as winches, and a network of steel wires and thick coir ropes transmit torque and rotation as smoothly as any high-end machinery. Traditionally the domain of Moplah Muslims, Hindus and even Christians have since joined the cadres of this exclusive band of muscular, energetic men who trace their lineage a long way into the past. Be that as it may, Beypore has nevertheless lost its premier position as a shipbuilding centre. Today, only a few boatyards remain — sitting on the banks of the Chaliyar River estuary churning out an occasional vessel for an Arab Sheikh with nostalgia for days

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leaveyou your valuable query here. I am Happy to assist you